The colonial roots of inequality

How

Colombia’s

education

system

reproduces

historical

social

and

ethnic

divisions

today

Colonial institutions such as slavery and encomiendas were the cornerstones of the wealth of elites and ethnic segregation in former colonies such as Colombia. Here, Juliana Jaramillo Echeverri of the Colombian central bank discusses her new working paper, recently edited by the Standard Error team, on how the education system continues to reproduce Colombia’s historical divides.

Education is the fundamental mechanism for human capital accumulation, which allows social mobility between generations, the overcoming of poverty, and alleviation of inequities. But in Colombia, as in other developing countries, access to high-quality education has historically been unequal, with vulnerable social and ethnic minority groups being the most affected. To shed some light on the historical roots of this inequality, a recent publication in the Colombian Bank of the Republic’s (BanRep’s) Economic History Notebooks (Cuadernos de Historia Económica) series analyzes the contemporary presence of specifically Indigenous, Afro-Colombian, colonial elite, and modern elite surnames in educational institutions of varying quality. The study, coauthored by Juliana Jaramillo Echeverri, a researcher at BanRep, evaluated the current positioning of several historical groups in the country’s educational system.

In the study, the surnames of the colonial elite correspond to rare surnames of 17th-century encomenderos, to students of Colegio Mayor Nuestra Señora del Rosario and Colegio San Bartolomé in the 17th and 18th centuries, and to slavers from the first half of the 19th century. The surnames of modern elites, for their part, correspond to the names of those who founded commercial banks during the 1870s and the Jockey Club in the first years of the 20th century.

Colonial institutions, such as encomiendas and slavery, left long-term effects at both the national and subnational levels and contributed to the persistent lack of social mobility across generations associated with the differences in access to high-quality education that we still see to this day.

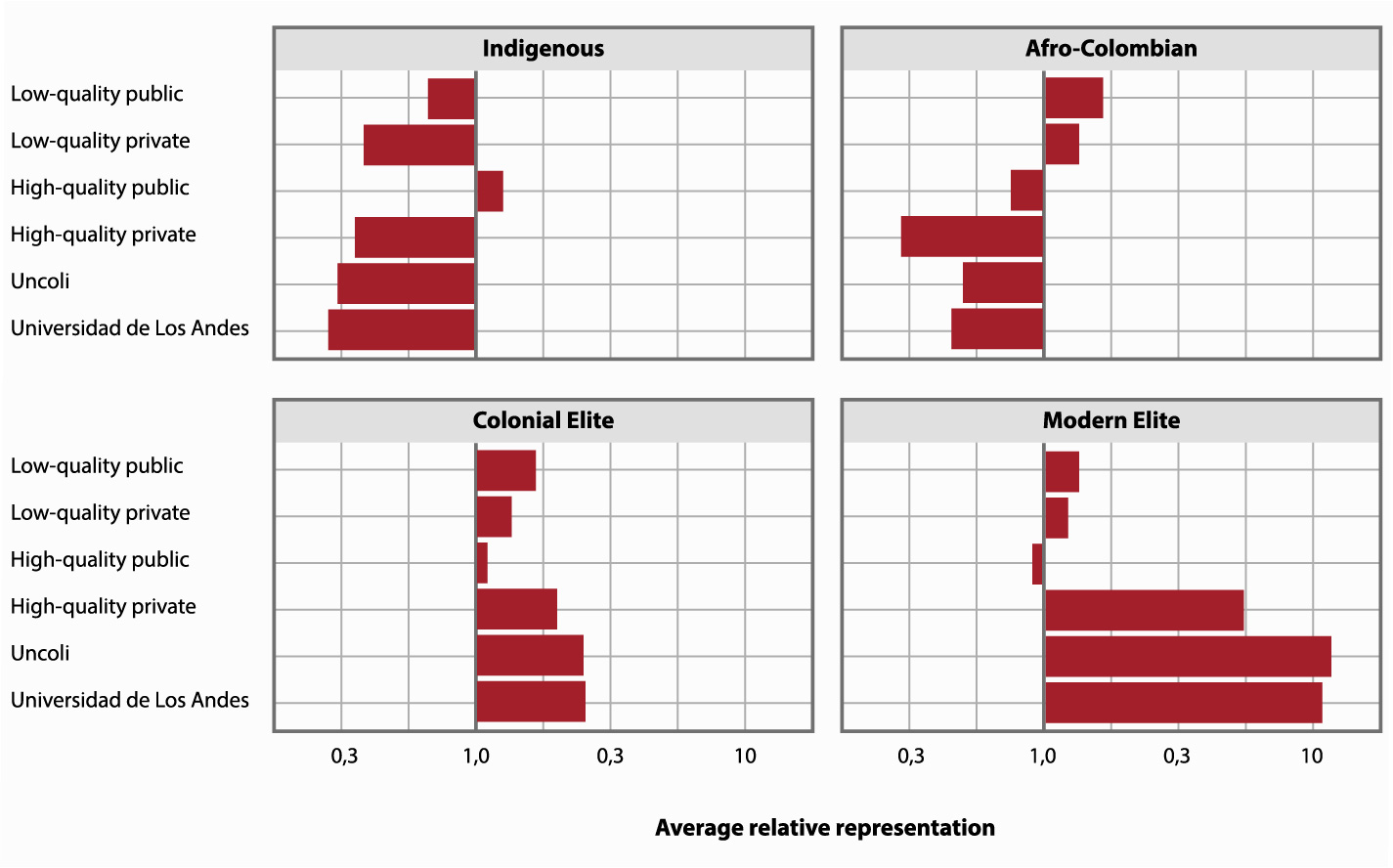

Using information from Simat (Colombia’s integrated enrollment system) and Icfes (the Colombian Institute for Educational Evaluation), the authors define an indicator of relative representation by the ratio between the share of a surname in an institution and its share in the total population of students registered in Simat. An indicator value above (below) 1 means that the surnames in question are overrepresented (underrepresented) in the institution of interest. Institutions are grouped by quality and public/private status. High- and low-quality institutions correspond to those in the upper and lower 5%, respectively, in state exams. Moreover, the authors examine schools belonging to Uncoli (the Union of International Schools of Bogota) and the University of Los Andes—all high-quality institutions traditionally attended by the country’s elite.

Figure 1 shows the average relative prevalence of the different historical groups in different types of educational institutions. It can be seen that the relative representation of elite surnames is above 1 in high-quality institutions while the opposite is the case for ethnic surnames. Members of the modern elite, for example, enroll at the schools affiliated with Uncoli at 12 times the rate of the general population of students, while the rate of enrollment of Indigenous people in the same schools is only 30% of their student population share. The surnames of colonial elites, for their part, appear overrepresented by a factor of nearly 3 in high-quality institutions. Indigenous surnames are slightly overrepresented in high-quality public schools. In low-quality institutions, elite groups appear slightly overrepresented, while ethnic minority groups show a distinctive pattern: Afro-Colombians are overrepresented, and Indigenous people are relatively absent.

Figure 1. Average relative representation of social groups in educational institutions

The results of the study suggest persistent inequality in access to high-quality education that has deep historical roots stretching back to the 19th century and beyond. This persistence of status has been dissimilar among the different groups, which underscores the need to understand how the economic and social status of different groups changes or is maintained over time. The results are also consistent with the historical literature finding that colonial institutions, such as encomiendas and slavery, left long-term effects at both the national and subnational levels and contributed to the persistent lack of social mobility across generations associated with the differences in access to high-quality education that we still see to this day. These results contrast with what we observe in countries with high coverage of high-quality public education, which typically plays a foundational role in achieving the best results in matters of equity and intergenerational social mobility.

Editor’s note: This post was originally published on November 27, 2023, under the title “Persistence in education inequality in Colombia: A historical analysis” on the blog of the Bank of the Republic of Colombia. The post was translated by Samantha Eyler-Driscoll and is reprinted here with permission.